By Hugh Bredenkamp

Low-income countries face vast development needs. One of the biggest impediments to rapid growth is a massive “infrastructure deficit.”

In sub-Saharan Africa, for example, indicators of road and rail infrastructure are only about half those in developing countries as a whole—comparisons with advanced economies, of course, would look even bleaker. Insufficient power generation capacity and telecommunications networks are also a big constraint. It is clear that large-scale investment programs, sustained over many years, will be needed to close these gaps. Both private and public sectors will have a role to play.

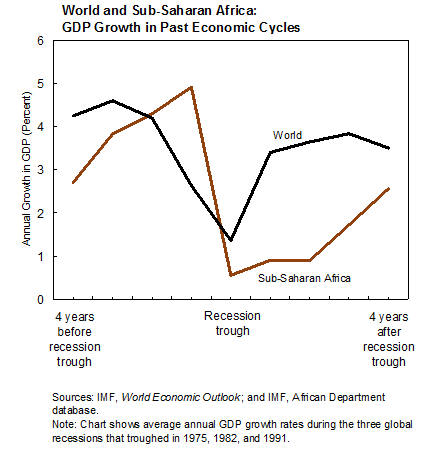

The snag, of course, is that investment spending typically has to be financed by borrowing, and until quite recently, the ability of low-income country governments to take on more debt has been severely hampered by legacies from the past. Many had built up unsustainable debt as a result of bad borrowing and spending decisions, poor project implementation, weak revenue systems (governments could not collect the taxes needed to service the debts), and often bad luck (as their economies were hit by global shocks). In effect, these countries were caught in a debt trap.

Infrastructure remains a big problem in many low-income countries (photo: Reuters)

But the world is changing. Large-scale debt relief, as well as big improvements in policies and public institutions, means that an increasing number of countries can now ramp up investment spending more efficiently than in the past, and borrow more aggressively for that purpose. They are starting with a clean slate. But not all countries are at this point. In fact, the majority still have more to do to on the policy and institution building front, and will need to borrow cautiously in the interim. Nevertheless, the greater diversity we see now among low-income countries needs to be reflected in how IMF-supported programs are designed (alert readers will notice that this has been a theme in my blogs this week).

What does this mean in practice? Well, for a start, we need a more flexible policy for setting limits on government debt in programs. For the past 30 years, the traditional low-income country program has permitted only highly concessional borrowing (that is, on subsidized terms), which generally rules out financing from the private sector, or from lenders who are not willing or able to provide sufficiently generous terms. There were case-by-case exceptions, but this was bascially the way it worked.

We are now moving (effective in December) to a new framework with built-in flexibility, linked directly to the circumstances of individual countries. Those with the lowest debt vulnerabilities and strongest capacity to manage public resources (assessed on the basis of widely-used indicators) will have much greater leeway than in the past to pursue borrowing strategies that mix concessional and nonconcessional sources of finance.

Continue reading →

Filed under: concessional lending, Economic Crisis, Low-income countries | Tagged: borrowing, concessional lending | 1 Comment »